Rubljovka Riches

My nonexistent readers will remember that I wrote about Russian capitalists in last year’s post St. Pete’s Wicked Ways. German documentary filmmaker Irene Langemann’s new project Rubljovka has been making waves in Russian circles for shining light on the same subject. The film concerns Rubljovka Road, an avenue in Moscow that is the equivalent of Manhattan's Park Avenue, but extending 31 kilometers all the way into the wooded countryside. The road is where Russian elites live—where they must live if they’re really anybody—and is populated by politicians, real estate barons, oil magnates, and other unpalatable types. Having a pile of rubles does not automatically earn one entreé to this real estate—houses cost at least three million euros and full estates can soar to twenty million. Residents include billionaire and Chelsea FC owner Roman Abramowitsch, fur designer Helen Yarmak, and Boris Yeltsin’s daughter Tatiana Diatchenko. Langemann portrays these people living decadent fantasy lives and ignoring rampant poverty among their fellow citizens.

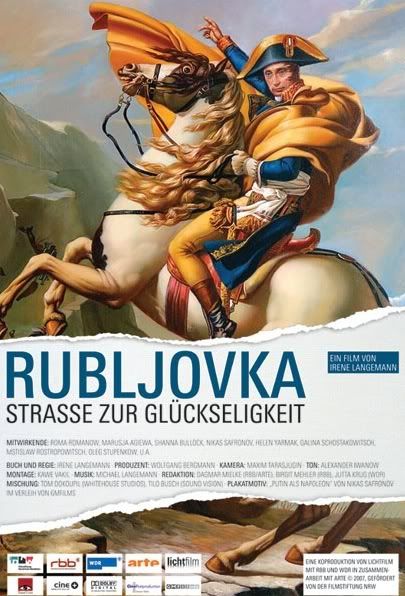

Vladimir Putin, a Rubljovka Road resident who is depicted as Napoleon on the film’s poster, is not happy with Langemann’s view of his nation. Her film is sprinkled with shots of Russian nouveau riches cavorting on ATVs and ripping around Moscow in Lamborghinis, images which are presumably juxtaposed against rickety old peasants brewing borscht. Much of the blame for this resides not with Putin, but with his embarrassing predecessor Yeltsin the dancing bear, who ushered in the legions of shock capitalists who crippled Russia. Nevertheless, Langemann’s portrayal suggests that Putin is disinterested in reining in

greedy developers who commit acts of violence against dirt poor Rubljovka Road residents who refuse to sell out. The Rubljovka website explains: The last remaining huts of the poor are swept aside to make way for the palaces of the wealthy by means that could not be any more unfair or brutal. The Russian State, celebrating an imperial comeback bolstered by petro-billions, has declared open season on the weak and poor. That last sentence is incorrect, of course. It was Yetsin's capitalists who declared war on the weak and the poor, and when they were done thirty percent of the nation had descended into poverty. This percentage has decreased under Putin, even if he isn't particularly sympathetic to the poor who happen to live on his block.

greedy developers who commit acts of violence against dirt poor Rubljovka Road residents who refuse to sell out. The Rubljovka website explains: The last remaining huts of the poor are swept aside to make way for the palaces of the wealthy by means that could not be any more unfair or brutal. The Russian State, celebrating an imperial comeback bolstered by petro-billions, has declared open season on the weak and poor. That last sentence is incorrect, of course. It was Yetsin's capitalists who declared war on the weak and the poor, and when they were done thirty percent of the nation had descended into poverty. This percentage has decreased under Putin, even if he isn't particularly sympathetic to the poor who happen to live on his block.Perhaps you’ve noticed that everything Russian seems to have a spy movie twist to it. The Max von Sydow plot complication here is embodied by millionaire art dealer Alexander Esin, who met with the film’s producer Wolfgang Bergmann in Frankfurt in September and offered 50,000 euros for the exclusive distribution rights to the film, with the exception of Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland, where the rights had already been sold. Esin said he wanted to establish a documentary channel and thought Rubljovka would make an ideal addition. Bergmann later told Speigel magazine: “No one else would have given me so much money.” But instead of distributing the film, Esin vaulted the project—his offer was a ruse to keep the film from reaching wider audiences. He later asked for worldwide distribution rights, even in the countries where they had already been sold. When Bergmann and Ingemann, refusing to be fooled twice, said no, Esin turned cold according to Lengemann, and delivered the perfect B-movie villain line: “You don’t know how difficult it’s become in Russia to get permission to film.”

Not to judge, but Bergmann and Ingemann should not have fallen for Esin’s initial offer. Esin is an art dealer. If that isn’t reason enough to be suspicious, he’s a millionaire art dealer. In St. Pete’s Wicked Ways I mentioned the disappearance of thousands of priceless artifacts from the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. The odds that some of those national treasures ended up in Esin’s hands, and were later funnelled through his company, seem pretty good. I’m drawing conclusions, to say the least, but so is everyone else. Langemann and Bergmann claim that Esin promised to address the Rubljovka distribution issue in February, which has led to the suspicion that his buying the rights is a scheme to protect Putin ahead of the presidential elections in March. This saga is yet another example that criminals are the most cunning people. I left Russia without a single priceless artifact, not one crown jewel or Fabergé egg, which shows what a dumbass I am, despite my high IQ. At any rate, hopefully Rubljovka will see distribution next year outside central Europe. At the very least maybe it will appear on You Tube.

Not to judge, but Bergmann and Ingemann should not have fallen for Esin’s initial offer. Esin is an art dealer. If that isn’t reason enough to be suspicious, he’s a millionaire art dealer. In St. Pete’s Wicked Ways I mentioned the disappearance of thousands of priceless artifacts from the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. The odds that some of those national treasures ended up in Esin’s hands, and were later funnelled through his company, seem pretty good. I’m drawing conclusions, to say the least, but so is everyone else. Langemann and Bergmann claim that Esin promised to address the Rubljovka distribution issue in February, which has led to the suspicion that his buying the rights is a scheme to protect Putin ahead of the presidential elections in March. This saga is yet another example that criminals are the most cunning people. I left Russia without a single priceless artifact, not one crown jewel or Fabergé egg, which shows what a dumbass I am, despite my high IQ. At any rate, hopefully Rubljovka will see distribution next year outside central Europe. At the very least maybe it will appear on You Tube.Labels: Rubljovka, russia, Vladimir Putin

1 Comments:

You are absolutely right, this is much better than anything I try to contribute lately. Dang, just need some rest.

Any plans for the the end of the year? Holler back, player.

Post a Comment

<< Home