Slur Slips from Arza's Mouth

In a little-reported story out of Florida this week, state representative Ralph Arza left a message on a colleague’s voicemail in which he angrily referred to a third party as a nigger. You’ll notice something interesting about that previous sentence—the use of the word nigger. You don’t see it in print much. So at this juncture I’d like everyone to take a good long look at it.

Did everyone survive?

Arza, a republican who had behaved in exactly this fashion on a previous occasion, responded to this latest public flap with: “At times I have had difficulty controlling my emotions and anger. I have noticed that this problem is made worse on those occasions when I have been drinking. Saturday night was one of those occasions.”

So we have another public figure trying to suggest that alcohol made him a racist. As a person well-acquainted with both alcohol and racism, I’ll suggest that someone is a racist before they consume alcohol. Booze may loosen inhibitions, but it does not change one’s beliefs. Mr. Arza hates niggers all the time—he just isn’t stupid enough to admit it without a vodka assist.

I have friends in Arza’s home state of Florida and they confirm what is already well documented—it’s a stronghold of American racism. The farther north from Miami one ventures, the more overt it becomes. One white friend of mine who moved to Jacksonville from Los Angeles tells me he is constantly astonished how often “nigger” gets aired in a room where no blacks are present. So it’s possible the word slipped from Rep. Arza’s mouth because he simply forgot he wasn’t speaking to someone in his normal peer group.

Let's agree to forever hereafter call these sorts of episodes “pulling a Mel”, because like Gibson, Arza quickly issued a contrite and embarrassed apology, followed by a pledge to enter rehab and seek counseling. So in addition to asking us to believe his scripted apology wasn’t written by his press secretary, he wants us to believe six weeks of country club rehab can cast the evil from him the way Satan was driven from little Regan MacNeil in The Exorcist. Nevertheless, I don’t personally believe racism makes Arza bad—only flawed. Life is a journey to better oneself and Arza may have taken a big step if his apology was indeed sincere.

While it’s easy to hope that an individual will one day escape the ghetto of the mind, it’s more difficult to imagine the same can happen to an entire culture. In black culture (if we accept for a moment that uniformity exists in any culture) there is a glorification of the word nigger. Among a large segment of urban and young blacks the word nigger—or “nigga”—is akin to a vocalized pause, on par with “like” or “dude.” Among the middle and upper class the word is less prevalent, yet there’s widespread acceptance of (if some exasperation with) its usage by other blacks.

I’m not here to suggest that such glorification is wrong—those who do it have an associated rationale and people have the right to express themselves as they wish (unless they are congressmen who represent a constituency). I do notice, however, that to glorify the word nigger yet continue to allow it to possess almighty negative power when uttered by non-blacks is confusing to most observers of black culture. The rules are writ thus: usage of the word nigger/nigga is fine among blacks, but the moment a white person uses the word it’s an act of war.

Though the guidelines regarding usage of this racial epithet are convoluted, they aren’t unique. The idea that the meaning of a word changes according to who uses it is universally accepted. For instance, you might endearingly refer to your little brother as “fuckhead”, but if someone else does the same it’s time to fight. However, in any reasonable family the realization that outsiders have taken to referring to your brother as fuckhead would cause you to reconsider your usage of the term. You might even stop doing it. You might even give up insulting your brother and instead try to be supportive and positive. And if you failed to do so, others might believe that you had sacrificed the moral authority to chastise others for calling your brother fuckhead.

But populations don’t behave like individuals—at least not quickly. Since certain segments of black culture relish (and profit monetarily from) usage of the word nigger, and certain segments of non-black culture refuse to relinquish the illusion of power usage of the word bestows upon them, what is the solution for a black person who wishes to escape these constant reminders of his/her low status? Well, in my case, I simply left the United States. I didn’t do it for this specific reason, but it was in the back of my mind that escaping the racial crossfire might be an illuminating facet of the expatriate experiment. As it turned out, it wasn’t just illuminating—it was the best thing I ever did for myself.

And I’ll discuss why as these postings continue.

.

Venezuela and Guatemala Stand Down

Venezuela and Guatemala today mutually ceased their efforts to win a coveted seat on the U.N. Security Council. Both have opted to support the selection of a third country—yet to be named. The stand-down is a blessing for the United States, who had been forced by Venezuela's hard drive for a seat to reveal to the world once again that when democracy and profit part ways, America sides with profit. Hugo Chavez had envisioned the seat as a platform from which to espouse his policy of social democracy, and to continue to be a general nuisance to George W. Bush. But the U.S. supported Guatemala for the simple reason that they’d rather have any country occupy the seat than Venezuela.

I lived in Guatemala for two years, and though it is a place I love, it’s also one of the most corrupt and dangerous countries in the world. Presidential approval ratings there are abysmal. The U.S. State Department warns that Guatemala is one of the countries in the world most likely to collapse. The ethnic minority in Guatemala (the Maya, pictured above) are one of the most oppressed in the hemisphere and were victim to ethnic cleansing by a U.S.-backed dictatorship. The U.S. government’s own USAID

website explains conditions there best: “Common crime is rampant, and corruption is endemic, fueled by increased money laundering, drug trafficking, and smuggling of illegal aliens.” The site goes on to say: “Unfortunately, the absence of an effective judicial system, the legacies of its civil war, as well as ethnic and social tensions, offer ample kindling for conflict that is increasingly expressed through violent acts such as lynching.”

So if Guatemala is so dysfunctional, yet still enjoyed U.S. backing, Venezuela must be worse, right? Well, that’s what George W. Bush would have you believe, but the simple truth is that U.S. enmity toward Venezuela derives from one fact—president Hugo Chavez is bad for business. He is nationalizing the Venezuelan oil industry and using profits to provide healthcare, education and training for low-income workers. Or more to the point, he is empowering Venezuelan peasants at the expense of rich oil barons. By opposing Chavez the U.S. proved that, while it bleats catchphrases such as freedom and human rights, it doesn’t actually care about them save in the ways that their promotion can generate wealth for U.S. oil interests.

As of this writing, the U.S. still monetarily supports repressive regimes in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Jordan, and other countries. So clearly, U.S. foreign policy is not driven by a moral mandate to promote democracy worldwide. In fact, they actively oppose democracy any time it suits them. In 2002 Chavez survived a coup attempt which he accused the United States of orchestrating. The evidence he cites is mostly hearsay, however it wouldn’t be the first (or even tenth) overthrow the U.S. arranged, and some believe George W. Bush tipped the American hand when, in the face of international condemnation of the coup, he actually extended diplomatic recognition to the illegal government. The gasp of incredulity in diplomatic circles was audible worldwide. What audacity. The number of world countries, besides the United States, that recognized the illegal government was zero. That’s right—none. The U.S. hoped its stamp of approval would carry enough weight to stabilize the new government, but it didn’t work—the new rulership was immediately toppled and Chavez was restored to power.

Since Chavez himself led an abortive coup some years back, the failure of the 2002 attempt against him might strike those of a Buddhist bent as karmic. I say it’s simply ironic. And now Chavez probably realizes it isn’t so much fun to be on the recieving end of one. But coups aside, Chavez has won the presidency of Venezuela in open elections, not once, but twice. So when U.S. officials describe him as a dictator, they are simply lying. They lie because branding a foreign leader a dictator is their trump card; Americans automatically hate the figure in question without actually finding out the truth for themselves. This sort of willful ignorance contributes to the worldwide reputation of Americans as pious, uninformed loudmouths, and it also makes it easier for the denizens of the White House to flout international law. So, for the record, here are the hard and undisputable numbers on Hugo Chavez:

In a poll by IAVD (Venezuelan Institute for Data Analysis) conducted in March, 82.7% of the Venezuelan population looked favorably upon the job done by President Hugo Chavez. The percentages break down thus: 22.9% said he had done a regular to good job; 41.8% good; 18.4% excellent; 5.7% regular to bad; 5.5% bad; and 4.6% terrible. The same poll declared that 61.6% of those surveyed did not know who should be the primary opposition candidate in the upcoming December 3 presidential election. However, Julio Borges, from the Primero Justicia party, received 8.9% of votes, the highest of all opposition candidates. In response to broader questions, 58.8% of Venezuelans said that they believe the country is better off today because of the Chavez administration.

Results from another poll conducted by Consultores 21 differ from the IAVD results. 62% of those surveyed were favorable of the job done by the President, while approximately 38% were not. The difference in numbers between the two polls lies mainly in how the questions were framed. While IAVD grouped those who thought Chavez was doing a “regular” job with the favorable group, the second poll winnows out these basically nonplussed respondents by asking for explicit approval of Chavez, rather than merely a lukewarm response. But in either case, Chavez’s poll numbers are high (George W. Bush’s approval rating is 35%, and that’s low no matter how the questions are framed).

In case you’re wondering about the integrity of the political process in Venezuela, the August 2004 recall election was certified as fair and open by both the Carter Center and the Organization of American States, and in it, Chavez was reconfirmed with 59% of the vote (Bush won 51.7% of votes in the 2004 U.S. election). In electoral terms, 59% of the vote is a landslide. Since it’s clear that Chavez is a democratically elected and unusually popular ruler, it becomes obvious what is really the source of tension between the United States and Venezuela. That’s right—it’s another fight over oil. Venezuela is the world’s fifth largest oil producer, and a major supplier to the U.S. But Washington doesn’t like its oil (which somehow ended up under Venezuela instead of under the District of Columbia, where it belongs) in the hands of a man who is openly critical of American policy. Add to that the fact that George W. Bush’s oil baron poker buddies are profiting millions fewer dollars since nationalization required a renegotiation of their fat contracts, and it’s easy to see why ousting Chavez is an important U.S. goal.

But U.S. aims are at odds with the needs of poor indigenous people. And increasingly, the U.S. definition of freedom seems to be the freedom to work in a Nike sweatshop. Chavez’s unforgivable sin is that of giving a bunch of uppity brown peasants hope that they can rise above a U.S.-dictated economic ceiling. And it’s an idea that is catching on in other parts of Latin America, notably Bolivia, where Chavez disciple Evo Morales won power in yet another legitimate election. Hugo Chavez is no saint, and there is plenty of opportunity for him to go rotten—only time will tell. But in the meantime perhaps those buzzwords you hear Bush directing toward him—dictatorship, human rights, free market, oppressive regime—are an attempt to disguise the White House's real aim of generating more American oil profit.

.

Flags of Our Soccer Hooligans, Part 1

As my imaginary legion of readers out there have no doubt noticed by now, BlackNotBlack is about black-related subjects—social, political, pop-cultural, international—discussed by a person who escaped the United States, and the ghetto of the mind. It’s about participating in the world community and viewing events through the lens of that experience. No matter how well you think you know yourself, it is only from the outside that you see who you truly are. In a sense, it’s about getting outside your own skin. There are places in the world where your role in the social hierarchy is reversed, where you’re near the top, cops don’t pay you a bit of attention, and store owners’ eyes actually light up when you walk through the door.

Is this a revelation? No—black soldiers in WWI and WWII figured it out when they were shipped to Europe. Hundreds of black jazzmen felt it in Paris during the 50s and 60s. My favorite jazzman—Miles Davis—preferred Finland above all other countries. He said Helsinki was the only city in the world where he truly felt like a human being. The instant I read that I was ready to book a flight (and I did go to Finland a few years back, but that’s a story for a later post).

One place where you can get a 20/20 view of yourself from the outside is Iceland. I spent some time there visiting a stuntman friend during last year’s

Flags of Our Fathers production. The movie is about war in the Pacific, but the only place in the world that looks like the Iwo Jima of the 40s is the Iceland of today, so Clint and the rest packed up their gear and boarded a plane. My friend is pictured above (in a scene later cut from the film) and, as you can see, one of his stunts was to play a guy who stepped in the wrong place at the wrong time.

To say blacks don’t often go to Iceland is an understatement. If it’s any measure of how much I stood out there, consider this: I ran into Bjork in a hotdog line and she stared at me more than I stared at her. Bjork, we can assume, has met hundreds of blacks—just not in Iceland. She was dressed in a long faux fur coat and bright red stiletto boots. It was strange seeing her, because I'd had contact with her camp before. When I was editor of a magazine some years back we asked her publicity firm for some potential cover shots to accompany a feature we were publishing. We wanted unique images, not the usual handouts, and so after some back and forth, they sent us several featuring her in a not-quite sheer shirt. Using the magic of Photoshop, we were able to tweak the contrast and levels enough to bring out her nipples fully, enjoyed a good laugh over the possibility of actually publishing the shot, then opted for a more conventional cover which showed only her lovely face. This whole episode went through my mind as I was looking at her. It's always the most juvenile pranks that give us the greatest pleasure, isn't it?

Icelanders like to fight. Some of them might disagree with that statement, but they’d do it by breaking your elbows. They especially like to break the elbows of foreigners, and it warms a special chamber of their hearts when the victim is American. In fact, “Go home Yankee” is the Icelandic national anthem. This sentiment is a result, I’m guessing, of the immensely unpopular American military presence there (bet you didn’t know your tax dollars are funding troops in Iceland, did you?).

American blacks travel so rarely to places like Iceland that a local’s first guess about where you’re from will invariably be England. Second most popular answer: France. Third (for me): Jamaica. So if you’re black you’re probably not American, in the Icelandic estimation. You’re just a foreigner. They still want to beat you down, but only in the getting-to-know-you way that you all laugh off later while sharing a round of Guinness.

In a little hamlet on the east coast of Iceland called Hofn some friends and I decided to go out for a drink one Wednesday night. After a stop at the harbor to watch the northern lights, we located a bar. Icelanders rarely drink during the week, but we were surprised to find the place empty. More than that, it had been closed minutes before. The owner told us he had opened only because the local football team had called and begged him for a place to party that night.

The look I exchanged with my friends at that point could best be translated as: “Oh great.”

I don’t mind being kicked out of joints. Hell, I’ve been tossed from bars on three continents. But I don’t kick myself out just because trouble is on the way. So rather than find another bar we hung around. When the footballers rumbled in the door (only six, rather than the expected eleven, plus subs) they were, let’s say, astounded by my presence.

Most Icelanders speak some English, and so the usual queries ensued: Who are you? What are you doing here? Why don’t you get your black ass out of our bar but leave the woman behind (just kidding, they were only thinking that, maybe). I escaped this situation by answering each question in Spanish. These guys’ brains were like fish on ice in a dockside market. I completely baffled them. Classically educated guys, they were probably remembering that the

Queensbury Rules on combat state that you can’t kick someone’s ass if they are unable to comprehend your intentions. So while they grappled with the puzzle of how to translate "going to beat you like a mongrel dog" into something a Spanish-speaker could understand, we slipped out the door.

I don’t normally back down at such moments, but these were football players, and there were six of them to three of us (not counting my girlfriend). They were short, like mascots rather than athletes, but you saw how Zidane up and Zidaned that Materazzi bloke in the World Cup? These guys, if they had decided to headbutt me, might have hit me in the groin. Anyway, you don’t fight outnumbered six to three, even when your friend is a stuntman and a stone killer (sorry to blow your cover, Dan). We might have won, but on the other hand, one good shot on Ari (who is definitely a lover, not a fighter) and it would have instantly been six on two. Even having a killer at your side won't help you then. Real life ain't

Enter the Dragon. By now most of my non-readers, I imagine, are thinking Iceland is not a country to visit, but you learn more challenging yourself in a place like that than regurgitating cherry Jell-o shots on a beach in Cancun. Call me crazy, but I loved it there.

There were also some non-violent nights in Iceland (typical sunset pictured above), but those are (you guessed it) for a later post.

Labels: bjork, iceland, travel

Clan of the Drum

I lived in Guatemala for a couple of years, and while I was down there—in a city called Antigua—blackouts became part and parcel of my life. I never had any previous experience with them. I know there was a massive 1965 blackout on the east coast of the United States that plunged 80,000 square

miles into darkness. And supposedly, nine months later, there was a spike in childbirths in east coast hospitals. Apparently there was really nothing else to do when confronted by Armageddon. No lights meant Russian missiles, the end of the world, a last chance to party in the face of the apocalypse. Inhibitions vanished, skirts dropped, and nature took its course.

In Antigua, sometimes the blackouts didn’t happen for a few months. Other times the lights failed twice in a week. These spells typically lasted a few seconds, but occasionally the world went black and stayed that way. We crossed the river Lethe into a new reality; a million new stars appeared in the night sky. The primal self, safely housed in the convolutions of the brain’s limbic system, suddenly broke loose to howl at the moon. Man gave way to beast.

Most people who lived in Antigua already felt as if they’d stepped back in time. When the lights went out we simply got a chance to step a bit further back and become hunter-gatherers sharing folk tales around the ancient fire. Huddled around candles, people probed a little deeper, responded a bit more candidly, and revealed more. And interestingly, the volume of conversation dropped dramatically.

If I wished to consult a psychologist, he or she would probably suggest that these things happened because of subconscious fear. Darkness is cold, darkness is loneliness, darkness is death and dreamless sleep and other untold evilness. Surrounded by it we huddled for protection like a tribe. I don’t have the spare cash to actually consult an expert, so I’m going to go out on a limb and say this theory is correct—deep down we were driven to seek each others’ companionship for safety when darkness closed in.

The most interesting blackout I experienced occurred in the town of Monterrico. Three hours south of Antigua by car, Monterrico is a tattered, tropical community of high surf, black sand, and mañana beach culture that moves as slowly as coastal erosion. Usually a night in Monterrico means a meal at dusk in one of the shacks that serve as restaurants, and then late drinks and music in a shabby beachfront bar. But this time the electricity died and the rules changed just a bit.

Our group of twelve noticed the blackout had occurred as we walked along the beach after sunset to the restaurant Caracol. All along the shore candles wavered like tiny signal fires from the windows of houses and hotels. Caracol looked shut, but when someone in our little clan called hello the owner appeared with a lantern and began pushing tables together and lighting tapers. You don’t expect a party of twelve during a blackout, but she gave us four-star service by candlelight and capped off the meal by comping us a dozen free shots. Generosity, too, emerges in the dark.

After dinner we walked to a wood and thatch palapa-style bar called El Animal Desconocido. Like all the other places along the beach, El Animal had been reduced to stoneage technology. Henri, the owner, stood shirtless behind the bar, sweating heavily in the heat generated by the many candles he had lit. A steady buzz of conversation issued from the customers, perhaps twenty people divided into a half dozen separate cliques. Someone had brought a drum and he began playing it. Nothing strenuous, just a little background noise. But it was a welcome sound. You don’t realize how dependent the atmosphere of a bar is on music until you walk into one that lacks it. And as often as you hear drums in Guatemala, you can never appreciate them until they’re the only form of music available. It is not overextending the tribal analogy to suggest that the sound of the drum began to unify the occupants of the room.

Before long someone else took up the beat. He played loud and fast, sending riffs exploding up to the rafters, intensifying the energy level in the bar until people were driven to dance. This second drummer was really good. He really lit a fuse in the room. Actually, the second drummer was me, but I’m simply suggesting that people will usually ignore even a well-played drum except under the circumstances forced upon them by the blackout. With new rules in effect, the drum helped transform rabble into a community.

It went on like that for a couple of hours—my drumming, everyone else dancing, drinking, and sweating. All of our howling primal selves were loose. As in the great blackout of 1965 inhibitions vanished, skirts dropped, nature took its course. It was phenomenally exotic, entirely unforgettable, and though I was the only black person in the town, I was the same as everyone else inside the fragile bubble of that moment. Why did it happen? Perhaps it was the drumming, or the liquor, or the spell of Monterrico. But I think it was the blackout, the rules changing, and inhibitions evaporating as everyone formed a tribe to resist that oldest of enemies—darkness.

Many of the people at El Animal that night had never spoken to a black person before. They marveled that more didn't visit Guatemala. Because of my little act as an ambassador with a drum, they were convinced that their country needed more blacks. Shit, we were fun—we knew how to party. The few Guatemalan blacks—called Garifuna—lived in isolation on the Caribbean coast and were rarely seen. Now these rank and file Guatemalans were wondering about the Garifuna. They were primed to abandon everything they'd absorbed about blacks from years of watching old American sitcoms. They asked if any of what they'd seen was correct. I asked them: "Whenever Guatemala makes the international news, like CNN, do they get it right?" Everyone laughed at that. Of course they didn't get it right. They got parts right, but never the important parts. I told them it was the same for me. American television gets parts right, but not the important parts. My Guatemalan friends got it. The analogy stuck.

All this potential for change came from a blackout and a sweltering bar that had no music. You have to keep alert for these moments. It might be a blackout, or it might be something else, but when that doorway opens, stepping through it can change people's minds. Easiest thing in the world to do, and a hell of a lot of fun.

.

Labels: drums, guatemala, monterrico, travel

Muhammed Yunus Wins Peace Prize

Speaking of the top 10% of intellects, Bangladeshi scholar Muhammad Yunus was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize today for founding Grameen Bank—which lends money to the poor via the concept of "micro-lending"—and for his writings contending that ending poverty will end war. The award was something of a surprise because Yunus was thought to be in line for the Economics prize, even though people like former U.S. prez Bill Clinton and other heavyweights had backed Yunus for the Peace prize. By agreeing with Clinton and others, the Nobel Committee have sent a message about the importance of the fight against poverty.

After you get over your disappointment that Bono or Bill Gates didn’t win, you’ll probably say that Yunus’s poverty/war thesis is self-evident (particularly if you live in poverty yourself, like 12.6 percent of Americans, or 1 of every 8 people, according to

U.S. Census figures), but while the connection between poverty and crime is indeed pretty much self-evident, suggesting that the same dynamic exists between poverty and war is a giant leap forward into territory certain wealthy western nations do not want to explore.

The news of Yunus’s award will be greeted with a resounding thud in the United States. He’s Moslem, after all, and the screaming rightwingers will claim that the Nobel committee are a bunch of politically motivated eggheads whose work is aimed solely at eroding our wonderful way of life. But just keep that U.S. poverty figure in mind when someone tells you about all the advantages Americans possess. I’ve been around a bit and in many of the countries I’ve visited, people live better than Americans—i.e., safer, healthier, longer, more content, and with more freedom (I’ll discuss this in a later post).

Yunus’s award is good news, and another small victory for freethinkers. If you have any spare time, Google Dr. Muhammad Yunus and take a few moments to look over his writings. He has become one of a growing number of influential people who speak for the impoverished. He is yet another who warns that, though it may be easy to ignore the voiceless poor, if the plague of poverty is not cured, one day everyone on this planet may have to pay the piper big time.

And as for Bono, he deserved it too (after all, he helped convince the World Bank to totally write off 40 billion dollars of African debt), but maybe he'll get it next time.

The One Right Way

I've gotten pretty good at listening. This isn't in any way a boast—it's just true. Everyone seems to have something amazing to say. I've become an expert at cocking an ear and picking up these bits of human song. I listen even when I feel it may be a complete and total waste of time. Tends to drive my girlfriend a little crazy, because some people aren't used to being listened to, which means some truly flaky people have grown attached to me just because I was willing to sit still and hear what they had to say. But here's the thing—though many of them are indeed flaky, some are also quite wise.

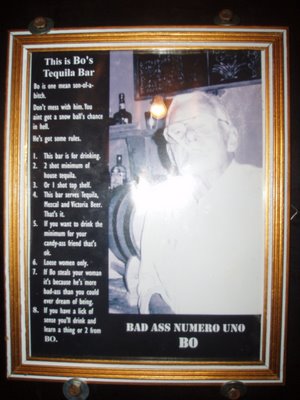

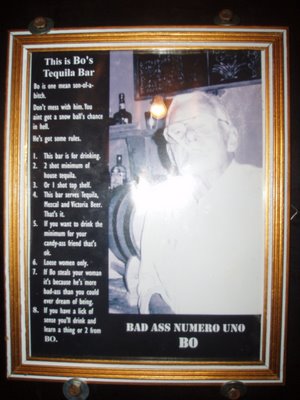

The person in the photo at top is named Bo. He ran an after-hours tequila joint in Antigua, Guatemala. His place was dark wood and candles, maybe twenty by ten feet in size, and strictly for experienced drinkers (that means people who can hold their booze without being loud, obnoxious, or annoying to women). Bo told me he left home when he was seventeen and never went back. Check the picture, and check the white hair—he’s been away from home (I’m guessing) sixty-five years. Two things were clear as I spoke to him—he loved traveling, and he loved running his bar. He helped me to understand once and for all that home is a mental construct, nothing more or less, and it has no inherently beneficial or detrimental qualities.

The person pictured second is named Miguel. Originally from El Salvador, he spent some years in the States, worked a bit, gangbanged a lot, and eventually murdered two people. U.S. policy on illegal immigrants who commit felonies is to deport them. At the time of this photo Miguel had served his sentence and was free, but was begging for change on the streets of San Salvador. In his closed right fist he’s holding his four front teeth. He told me they’d been knocked out long ago, but he hated to part with them. From him I learned that home is a real place, not a construct, and leaving it may be the worst mistake you ever make.

Two people—both left home young, experienced opposite results. What it indicates to me is that there is no one answer, and no one way to live. Everyone wants to shout answers from a mountaintop. I’m here to say there are no answers. Daniel Quinn discusses this in an interesting book called

Ishmael. He suggests, and I agree, that one of our biggest conceits as human beings is the belief that there is one right way to live. There isn’t. And the refusal to accept that there isn’t is a contributing factor to the millennia of warfare and misery our species has suffered.

My way is not the right way, it’s just my way. My way is about escaping the ghetto of the mind. Bo and Miguel are two of the people who await outside the walls. In other circumstances, in another place and time, I believe Miguel could be the person running the bar, and Bo could be the street hustler. That belief is the reason I see them as equals, and it's why I give equal weight to their diametrically opposite forms of wisdom.

Bo died a couple of months after I left Guatemala, but the news off the wire is that he died in bed and they found a condom and an unredeemed coupon for a Swedish massage in his pocket. The most important thing I learned from Bo was Bo’s rules, which I discovered applied equally to his bar and to life. They were posted on the wall for all the customers to read. I hope they’re still there. Highlights:

#1: This bar is for drinking.

(substitute “life” for “bar” and “living” for “drinking”)

#5: If you want to drink the minimum for your candy-ass friend, that’s okay.

(nothing to add to that, really)

#8: If you have a lick of sense you’ll drink and learn a thing or 2 from Bo.

Labels: el salvador, guatemala

Just Peeking

This is my introductory post, my tentative entrance onto the stage, the moment when I sneak one eye to the curtains and peek through. What a spectacle to behold. It's all racket and white noise out there.

But that's just fine.

Yes, I am publishing a blog, and yes, I am late late late. But deciding to publish a blog was an easy choice for two reasons—most blogs are dull, if not unreadable, and most black blogs make blacks look bad (yes, I eschew the clumsy terminology "African-American" but am open to something better than just "black" if you have any ideas). It occurred to me that a blog shouldn't make its presumed beneficiaries look like cretins, so rather than accept affairs as they stand I decided to add my voice to the din. I'm drawing courage for this endeavor from the fact that amid the utter pandemonium of the web my output will be little more than a faraway voice in a howling wind. I can say whatever I like because nobody will hear me.

So, mindful that there isn't a soul listening, I imagine that I might be asked why the blog is called BlackNotBlack. I've got no idea why—it's rhythmic, and the name was available. In retrospect I see that I might have chosen better. For instance, BlackNotBlack can be perverted into BadBadBad, or CrapCrapCrap, but then I remind myself—nobody will make fun of the name because, though there's a huge crowd out there, nobody is looking in my direction.

I might also be asked who the blog is for. That's a question I can answer: Theoretically, it's for people like me. I'm unmarried, college-educated, and well-traveled. I wanted to do what Hemingway or John Huston did, not rock a mic or be like Mike. I've lived outside the United States, which is something a lot more blacks should do, and which I'm going to reference extensively. I don't draw authority from the fact that I make a lot of money—bling is the thing, but it's just an illusion. I don't draw authority from the presumption that I speak God's word—because that is another illusion, and a particularly crippling one for blacks in the U.S. I don't claim any authority at all—I would never do that, because that would mean I wish to exercise power over you.

I definitely don't want that.

At some point during my life and travels I came up with a little game—the Ten-Second Video Moment. Whenever I found myself in a unique situation I imagined it as a pirate signal that I could beam to people. They would see what I saw, experience it from my point of view, but only for ten seconds. Example: you're on the second deck of a giant ferry, fifteen foot seas are breaking over the bow, the deck is pitching so hard people are holding on for dear life, everyone is freezing and soaked to the bone, most have vomited at least once, you're barely managing to hold together a shoebox that is disintegrating because it's so soggy and which contains two angry coatimundi, and if they get out they'll either drown (preferable), or they'll be seen and you'll be arrested for smuggling (not in any way preferable).

See what I mean? Admittedly, nothing contained in that ten second moment qualifies me to post my opinions, but it's an interesting moment nonetheless, no? I mention it because it's related, if only metaphysically, to the concept of blogging. How? Let us simply say that classrooms produce good technical thinkers and writers, but life experience molds thinkers and writers who are better than simply technically proficient. Or put another way—I’ve been around. Having been around is always most useful when you least expect it.

So here's what BlackNotBlack is about—escaping the ghetto of the mind, cracking open the bones of existence and sucking the marrow clean out. BlackNotBlack is about thinking freely. It's about how I think. It's about how the way I think is not subject to the control of others, but rather is a process that I have willfully shaped into a philosophy of how life should be lived by one small, insignificant black person on this planet—me. The philosophy has been road-tested, safety-rated, exposed to inclement weather and ill fortune, and has come out as shiny and flawless as a gemstone. It works perfectly for me. It has gotten me into the exact type of trouble I love and out of the exact type of trouble I fear. I post it here for other free thinkers to examine, and for those who perhaps don't think freely to consider.

In a little-reported story out of Florida this week, state representative Ralph Arza left a message on a colleague’s voicemail in which he angrily referred to a third party as a nigger. You’ll notice something interesting about that previous sentence—the use of the word nigger. You don’t see it in print much. So at this juncture I’d like everyone to take a good long look at it.

In a little-reported story out of Florida this week, state representative Ralph Arza left a message on a colleague’s voicemail in which he angrily referred to a third party as a nigger. You’ll notice something interesting about that previous sentence—the use of the word nigger. You don’t see it in print much. So at this juncture I’d like everyone to take a good long look at it.