Misterioso Spotted?

Check the immaculately groomed mustache. Dig the glowing suit and matching panama hat. Has Sr. Misterioso resurfaced? He had been missing since arson gutted one of his homes earlier this year, but if this shot is any indication, the world's most dapper jet-setter is once again cruising the glittery beltways of the international scene. It can only mean that he successfully hunted and destroyed the villains responsible for the attempt on his life, and is now engaged in some serious recreation. We don't know where this anonymous photo was taken—Miami? Ibiza?—but the instant fresh details come over the wire they will appear here, at BlackNotBlack. And let us be the first to extend a heartfelt: Welcome back, Misterioso!

Labels: señor misterioso

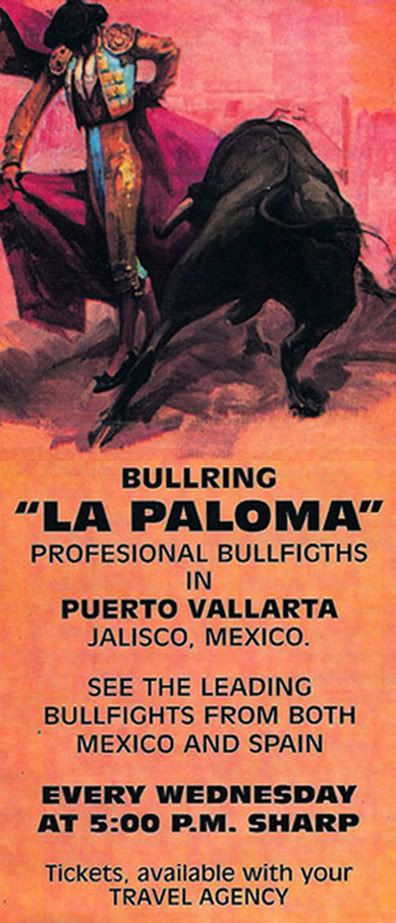

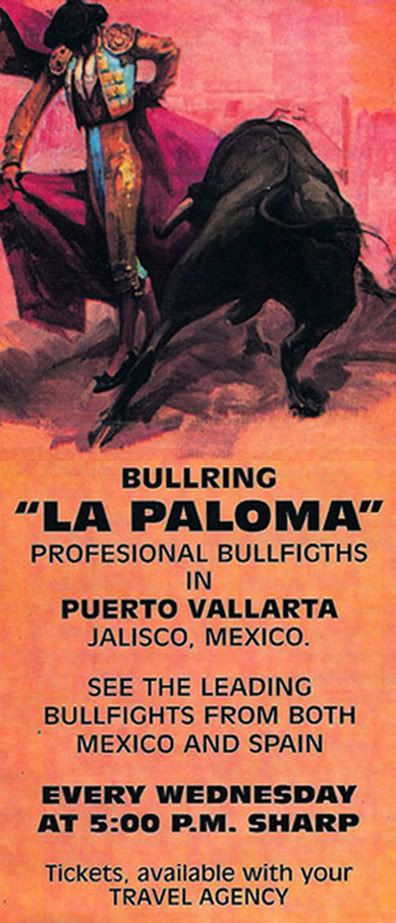

Brave Old World

The bull was named Colon—Spanish for Columbus—and when the

picador speared it from horseback, a gout of blood gushed from between its shoulders as if from a fountain. All the most basic elements were finally extant in Puerto Vallarta’s

plaza de toros—dirt, threatening purple sky, the shiny black hide of the bull, and now blood. Behind me a schoolgirl burst into tears at the sight. From American tourists I heard angry complaints that it wasn’t fair. They were talking about how the

picadores entered the ring riding armored horses and, with the professional aplomb of S.W.A.T. snipers, speared Colon while safe atop their mounts. How could that be fair?

Personally, I thought for any

gringo to talk about fair fights was laughable. As a culture Americans—throughout a history of conflicts both noble and ignoble—have proved to be little concerned with fighting fair.

Como se dice “hypocrisy”

en Español? And anyway, a bullfight isn’t supposed to be fair. That’s what few in the crowd seemed to realize. “Matador,” after all, means “killer.” To an aficionado, calling a bullfight unfair is like telling a baseball fan it isn’t fair that the pitcher throws so hard. The bullfight isn’t so much a true fight as it is a juxtaposition, an entwining of ballet and savagery. Fairness has nothing to do with it. That’s why the

picadores spear the bull, shredding muscle in animal’s thick neck so it can’t raise its head—it gives the matador the edge he needs to do battle with a creature that would ordinarily smash him flatter than a corn tortilla.

It’s also why there are apprentice matadors called

toreros helping torment and tire the bull before the real fight begins. The bull must be weakened, physically diminished. All the attendant pomp—the

picadores, the shrill mariachi band which provides musical commentary on the proceedings, the gaudy

traje de luces or suit of lights the matador wears—is rooted in tradition that dates back uncounted centuries. But as a wounded bull stands there wheezing like a massive bellows, covered in clots of gore, pissing uncontrollably into the dirt, it’s natural to see its situation as unfair.

Nevertheless the fight went on. Colon knocked down his tormentor, Pascual Navarro, trampling him and buffeting from his shoes and hat. But Navarro was not injured. He rose, killed Colon cleanly and was awarded by the

presidente—the fight judge who sits in the stands—both the bull’s ears as trophies. Above you see him holding up the grisly prizes and beaming at the crowd. For the Americans in attendance, if there was some artistry to the battle or some satisfaction to be derived from being spectators at this ancient rite, they didn’t care. They were aghast, and by the third fight many of them had left the stands.

Three matadors, three messily slain animals. Each fight appeared identical on the surface, but in reality each differed in its details. Some matadors attempted maneuvers others didn’t. Some bulls fought better than others. But all the animals ended up collapsing bloodily into the dirt.

The last and best matador was a young man named Valente Reyes, who was tall and slender as a prince. He elevated the butchery to something more like art. He performed

pases rodillas—passes from his knees—making a bull named Mago charge and miss five times. He swung his

muleta—his cape—in arabesque patterns like an illusionist. The Mexicans in the crowd erupted at these maneuvers and Reyes stopped in the middle of the duel to bask in the adulation, handsome and arrogant, as the bull glared dully.

In fact Mago seemed all but defeated. So when, on the next pass, his horns sliced open Reyes’ sequined

traje, it couldn’t have been more shocking. White linen hung from a slash in the brocaded costume and the matador’s façade of mastery briefly dropped. But as a chorus of cheers rose up from Americans who had stayed—the Mexicans shook their heads in disgust at this display of disrepect—Reyes rediscovered his focus. He taunted the crowd with a gesture that said, "Watch now, what I do to this bull you cheer." It was plain to see that Mago would be made into an example.

Reyes took up a pair of gaily decorated

banderillas. Covered with paper flowers, these short, barb-tipped sticks spur the bulls on because of the severe pain they inflict. Reyes faced Mago. A quick pass and the

banderillaswere deftly stabbed between the bull’s shoulders. It roared. Another pass and two more

banderillasbristled from Mago’s back. The bull was foaming at the mouth. The blood and paper flowers and churning dust of the spectacle were all an abstraction by now. What I was witnessing wasn’t surreal or un-real, but heightened reality in which bull and man had become combatant-ambassadors for their species. It was the cruelty of all humanity I saw, and the rape of all nature.

The remaining Americans, even those who had protested, were mesmerized now by the grimness with which Reyes conducted his business. He walked with his last pair of

banderillas to the edge of the bullring and broke them against the

barrera, the railing. They were now half as long as they had been—and would be twice as dangerous to insert. Another thunderous charge and the harpoon-tipped sticks went into Mago’s hide.

Mago had already proved to be a smart bull. He had backed away from the

picadores after being holed once, and it had been an unexpected but deliberate rotation of his massive head which had allowed him to nearly hamstring the agile Reyes. But in the next moment he proved just how smart he was. He looked around the ring for an exit. There could be no mistake about it. He made a half-circuit, staring at the

toreros, perhaps considering whether one of them would be easier to fight. Then he lingered at the spot where he had originally entered the ring. But there was no door there now.

Meanwhile Reyes had gone to his

mozo de estoques—his personal attendant in the narrow passage behind the

barrera called the

callejon—and retrieved his

estoque, his killing sword. The last act had begun. With exquisite patience Reyes incited Mago to charge. On the first pass his blade glanced off some bony cleft or other and fell to the dirt. Reyes recovered it and Mago wheeled about. A second pass and the blade missed the mark again. The Americans jeered and Reyes goaded them with a gesture from his upraised hand. He was angry again, and that meant Mago’s time was up.

On the third pass Reyes finally drove the

estoque in, high up on the bull’s back. Mago spun about from that last charge unaware that he was already dead. But the crowd saw the pommel of sword flush against his back and knew it was over. The bull’s heart had been pierced. Mago started to charge again, stopped. He paced about, bellowed loudly, and fell to his knees. A torrent of maroon aortal blood burst from his mouth and nose as if a faucet had been turned on. Reyes walked regally around the ring with arms aloft, pausing so that tourists with flash cameras could get good shots of his face. Mago fell on his side and stopped moving. Reyes earned two ears for his victory.

I knew from reading Ernest Hemingway’s

The Dangerous Summer—that blood-soaked classic about a season-long

mano a mano between two legendary Spanish matadors—that two ears were only half the trophies that could be awarded to a brave bullfighter. Reyes had probably earned those last two trophies—the tail and the hoof—a few times in his brief career. But as good as he was, even he would have been little more than a

mozo to the greats of Barcelona or Mexico City, those storied matadors who can kill a bull instantly with their swords, severing the spinal cord and stopping it in its tracks.

Hemingway rhapsodized about the festival of San Fermin—ocurring this last couple of weeks in Spain—in which the brave run with the bulls. He described a love for bullfighting that is remarkable in its lack of apology, especially eighty years later. Unlike portrayals in anti-bullfighting literature, he was fully aware of the cruelty of the sport, but saw it as a great human art in a chaotic and hellish world. In a world in which savagery is continually cloaked in artifice, it was the ultimate art, a truth in an ocean of deception. It represented a reality which he felt many were unwilling to face—that for us to hold on to our humanity, death must remain close to us, close enough to see and smell and hear, and at the expense of the bulls.

We are presumed by some to be the only creatures who are aware of death, of the void. This will turn out not to be true, as animal science continues its inexorable march, but in 1926, it was stone cold fact. Hemingway felt sorry for the bulls. But it was man's ability to cloak cruelty in ritual that impressed him. He described matadors performing tremendously artistic passes called

veronicas, mariposas, chicuelinas, and

remates. These were all techniques unseen in Puerto Vallarta. The most exceptional matadors even kneel in front of a bull and touch noses with it. No one in Puerto Vallarta would have dared such a thing. Vallarta is the minor leagues. But the

matador I observed—Valente Reyes—was young and ambitious, and might yet graduate to the great plaza in Mexico City. In a country where children fight bulls in pastures using t-shirts as

muletas, the craving for fame in the national sport provides considerable incentive to practice.

And so after the dust cleared and dead Mago was dragged out by his hooves, I wondered what I had actually seen. I wished I was in Pamplona. That was a given. But beyond that, did the animal agony I had witnessed remind me of the quality of suffering or did it desensitize me to it? Is tradition a justification for cruelty? And originating as I do from a land of carefully pre-packaged savagery, where a football knee injury is considered mortal and

mano a mano is when two hockey players square off to beat each other up, can I criticize this sport that does more than just

simulate death?

Some days later I described these events to a friend, and told him he should experience a bullfight one day. He said: “If I want to experience a bullfight, I’ll just go out in my back yard and stab a puppy.” It was a curt reminder that, poetic or not, a bullfight is simply mythic, organized slaughter. But nothing I’d seen before, particularly nothing in sanitized American sports, ever affected me as deeply as did the deaths of four Mexican bulls. And it made me think about things no boxing match or pit fight ever caused me to consider. I wonder if that isn’t the sole reason the practice has survived so long.

Perhaps the strangest part of it all is that the

plaza de toros in Puerto Vallarta is called la Paloma—the Dove.

Labels: bullfight, hemingway, mexico, pamplona, san fermin

Señor Misterioso: Travelling Companions, Part 2

Speaking of good luck charms and trusted companions, an even more intimate friend and indispensable component of my travels has been the enigmatic jet-setter known only as Sr. Misterioso. Described by some as an amalgam of Ricardo Montalbán and James Bond, he is in reality more Houdini than he is 007, more Cary Grant than he is Mr. Rourke. But whatever Sr. Misterioso is, and however people choose to see him, he is doubtless one of the most fascinating personages of our time.

While certainly no recluse, Sr. Misterioso is something of a cipher who has spoken of himself on precious few occasions. To do so would be boring—pure anathema to a creature so circumspect and mannered (this did not, of course, prevent an unauthorized Greydon Carter profile from appearing in

Vanity Fair in 1998). Because of Misterioso's cloak of silence, nobody knows for sure if his origins are cosmic or supernatural, but he first took earthly form in Rosarito, Mexico—that much is known. Which year this occurred is anyone’s guess. But it was in 2002 that Hollywood stuntman Daniel Forcey, while working on a film called

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, encountered Misterioso in a curio shop.

Forcey related the tale: "I was buying cigarettes or mezcal, I can't remember which, when I looked down at the counter beneath the cash register where, hidden amongst the super balls, zoom flyers and clown wigs, sat nestled a plain black and neon green package. At the top of this package were five words: "Senor Misterioso! He's so mysterious!" I knew right then and there I had to have him."

Since that meeting, Misterioso has accompanied both Forcey and I on our travels to Mexico, Guatemala, and Iceland (he has been known to join others, but only those capable of providing the thrills and danger to which he is accustomed). Misterioso appears and vanishes according to whim, always garbed in his custom-designed atomic suit, which some say was crafted by

Karl Lagerfeld, but which unnamed U.S. government sources say was actually created during a nuclear fission experiment inside an Area 51 atom smasher. Whatever the suit's provenance, it is legendary in fashion circles. Hanae Mori once shed tears of rapture at the sight of it. Jean-Louis Scherrer was critically ill for a year after a misguided attempt to incorporate radium into his own designs.

Like all celebrities, Misterioso has web cults devoted to him. One site states that he arose from obscure films, such as the 1966 Italian-produced

Misterioso Señor Van Eyck, and the 1943 Mexican obscurity

Misterioso Señor Marquina. Both attributions are false. There is a

MySpace page, of which Misterioso disavows any knowledge, though there are whispers he mave have had the page constructed to disseminate disinformation. It seems likely, considering the obvious errors in its content. For example, the page claims he is a secret agent here to save the world. This has been floated more than once as a reason for Misterioso's movements on Earth, but nobody knows for sure why he is here—he isn't saying. Also, to be an agent one would have to have masters—unlikely. Another error—the page claims Misterioso is hoping to meet Mrs. Misterioso. This hardly seems plausible, considering he is an avowed bachelor who has romanced Alessandra Ambrosio, Anne Heywood, Isabelle Adjani, Lisa Bonet, Devon Aoki, Princess Leia, Bjork (once during her Sugarcubes days, and a second time as a solo artist), and other women comprising a fruit cocktail of modern beauty.

One website asks: “Is Sr. Misterioso an extremely dangerous man or just a harmless socialite in a glowing suit? His motives are unclear, but there is documentation of meetings with extraterrestrials, Howard Hughes, George Steinbrenner, J.D. Salinger, Chuck Norris, David P. Reinhardt, and Pee Wee Herman.” While Misterioso

is a very dangerous man—when he speaks his mere words can sting like a whip and his gaze can flashfreeze watercress—his associations have never been as backalley as Pee Wee Herman. He has also asserted that he never crossed paths with Chuck Norris. He has stated explicitly that, as a man of taste, he doesn’t mix with opportunists, half-wits, or z-grade actors-turned-racist politicos, and would only meet with the likes of Chuck Norris to disintegrate him. As an entity with a Latin essence, it’s the least he could do. As for the Howard Hughes connection, that one is factual, but was a brief meeting in Macao in 1952—before Hughes lost his marbles—at which Misterioso introduced Hughes to aspiring movie starlet Maria Sen Wong. On the subject of extraterrestrials he is tantalizingly mum.

Misterioso is famously camera-shy due to several run-ins with overzealous paparazzi (who he was later forced to destroy), and from a need to protect the identities of some of the women with whom he trysts, who are often royalty. But when relaxed and enjoying himself among friends Misterioso is both talkative and willing to permit a snapshot or two. In the photo at the top of this post we see him reposing in one of his favorite towns, Ensenada. In the next shot he demonstrates the power of the force to attract smoldering space princesses. You may notice that Misterioso is out of focus. This is either due to radioactivity from the suit affecting the camera chip, or an autofocus problem caused by Misterioso's simultaneous presence in several dimensions at once. Indeed, by Misterioso's own declaration, any in-focus photo of him is a fake.

One last rumor should be cleared up—that the elimination of Sr. Misterioso and his atomic suit are of paramount importance to certain dark agencies. This is fact—one of his several earthly domiciles, an unassuming yet elegant mid-century modern south of Los Angeles, was recently consumed in a suspicious fire while he was inside. Nobody has seen Misterioso since, not

in his villa in Capri, nor his hacienda in Ixtapa, nor even his palapa in Canggu. But most have faith that he used his vanishing trick to escape the conflagration, and is even now hunting the suicidal fools responsible in order to blast them into slag. But this is mere speculation. In the end it’s impossible to know Misterioso’s plans or whereabouts—he’s just too mysterious.

Labels: alessandra ambrosio, mexico, princess leia, señor misterioso

Die Hard Cooler: Travelling Companions, Part 1

Yesterday my friend Charlie jingled me and asked if I wanted to go to the beach. Most people would welcome such an invitation, but the mere suggestion sent my pulse rocketing like someone had stuck a live wire in my heart. But then I remembered we weren't in Central America, which meant there would be none of the events associated with our most recent beach trips. There would be no shooting. There would be no judo matches in the pool. None of my friends would steal a horse. We would not snort salt up our noses and squeeze limes in our eyes. We were going to a sane beach, populated by sane people, and we would follow their example and behave in sane fashion.

Once my Central America flashback passed, I dug around in the darkest and most cobwebby recesses of my kitchen cupboard and found my treasured portable cooler. I brought the cooler to the beach and, as Charlie, Diana and I sat there together on the sand and sipped cold white wine, I realized this was possibly the most worldly tote in history. Comparing notes, we realized the cooler had traveled to many countries, nearly died three times, and had facilitated more than its share of debaucherous events. In a sense it is a totem, and an analogue of both Charlie and me.

The cooler originally came from Costa Rica, where Charlie purchased it in a hole-in-the-wall

tienda during a road trip. For some reason he and another friend, Peter, made a bet that between them they had to finish a bottle of liquor every night. If this sounds a bit excessive, all I can say is these are the kinds of bets you make when trekking through the third world. Anyway, the cooler was the medium of choice for transporting the booze. Its role as a facilitator of debauchery was thus established. Later in the trip Charlie's truck, below, sank in a swamp, and the cooler went down with it. In the photo Peter is sitting on the hood, navigating so that Charlie won't drive into a sinkhole. Obviously, Peter failed at this task not long after the photo was taken. Eventually the truck was rescued, but the waterlogged cooler was quickly beset by mold. Charlie put it aside and forgot about it.

Two years later, one idle afternoon in Guatemala, Charlie and I, along with our friend Breigh, found ourselves shooting stick in an extremely dodgy pool hall. By dodgy I mean that it was a filthy and sweltering cinderblock bunker frequented by shirtless and shifty-eyed gangbangers. There were no windows and the bathrooms were festering black bogs. I think the locals were pretty surprised we dared to show our faces in there, three

gringos—one of us black and another female. I said to Charlie, “These dudes think they’re going to bad vibe us out of here, but fuck that—I’m staying. They aren't going to bother us.”

Somehow this declaration evolved into a bet over pool, which I lost. But because we traded bets like stock shares, I took a wager our friend Abbie had lost to me the week before and traded it for my loss on the current bet. So Abbie ended up having to pay my bet. Strange, I know, but that’s how we do things. Anyway, the stakes of the bet were that for an entire night the loser would serve as the winner’s liquor caddie—essentially a personal valet loaded down with a night’s supply of booze. You can see why I traded out of this bet. Like a lot of black men, I just don't cotton to serving people. It's an ancestral thing. Perhaps you don't understand.

Do undertstand this, though—I adhered to the established rules within our group. So I didn't weasel out of paying—it was a legal and fair swap, even though Abbie was nowhere in the vicinity when it happened. She agreed to fulfill her duty, which was commendable, since within our group quite a few people lost bets they simply refused to pay off (usually involving full or partial public nudity). I once lost a bet of this variety—thumbwrestling, of all things—and was supposed to give a sort of public performance in a Speedo. For a week I cursed my own stupidity, but eventually the winner of the bet decided I could perform in a regular swimsuit. Thank the Lord.

Anyway, we knew we’d need quite a bit of liquor if someone was to caddy for Charlie. He'd decided the caddy had to serve anyone he designated, so Abbie was looking at supplying five or six people for the night, including me. Yes, that means I lost the bet, and somehow won it too, but Charlie was making the rules. I was just along for the ride. We pondered what to carry all this booze in. That’s when Charlie remembered the cooler, last seen sporting splotches of mold and smelling of swamp water, presumably one with the Earth by now. But Charlie found it a day or two later, and when I took a look at it, I decided we could clean the old girl up and use her.

It was a few weeks before we found a convenient night to settle our bet. By then the circus was in town, and since there is nothing quite as weird and unpredictable as a Central American circus, we just had to go. The night was also a going away party, because Charlie had decided to visit the U.S. for six months. We decided on our favorite cocktail—

cuba libres—as the libation of choice, which meant the cooler needed to be stocked with rum, Coke, ice, and limes. Quite a load. We also wanted to bring a bottle of mezcal a friend had purchased in Mexico. To make Abbie’s job easier we bought a second tote.

Charlie’s going away party was epic—expat send-offs usually are. The next day I was treated to a hilarious story about some dope eating a mezcal worm off the ground. Turns out the dope was me. The circus was a blast—I do remember that. But since I’m planning a post on Central American circuses, I won’t get into the details just yet. About the cooler all I can say is that it served nobly that night, like the good soldier it is. Since Charlie was leaving, he gave me the cooler as a gift and I’ve owned it ever since. I hadn’t used it since Guatemala, so when I pulled it out yesterday quite a few good memories came with it. The cooler has been a companion, a witness, and a good luck charm. It’s survived swamp, ocean, volcano, rain forest, and two near-fatal bouts with Central American mold. And after all it has been through, it’s still in prime condition—just like me.

Labels: beach, circus, gambling, guatemala

Check the immaculately groomed mustache. Dig the glowing suit and matching panama hat. Has Sr. Misterioso resurfaced? He had been missing since arson gutted one of his homes earlier this year, but if this shot is any indication, the world's most dapper jet-setter is once again cruising the glittery beltways of the international scene. It can only mean that he successfully hunted and destroyed the villains responsible for the attempt on his life, and is now engaged in some serious recreation. We don't know where this anonymous photo was taken—Miami? Ibiza?—but the instant fresh details come over the wire they will appear here, at BlackNotBlack. And let us be the first to extend a heartfelt: Welcome back, Misterioso!

Check the immaculately groomed mustache. Dig the glowing suit and matching panama hat. Has Sr. Misterioso resurfaced? He had been missing since arson gutted one of his homes earlier this year, but if this shot is any indication, the world's most dapper jet-setter is once again cruising the glittery beltways of the international scene. It can only mean that he successfully hunted and destroyed the villains responsible for the attempt on his life, and is now engaged in some serious recreation. We don't know where this anonymous photo was taken—Miami? Ibiza?—but the instant fresh details come over the wire they will appear here, at BlackNotBlack. And let us be the first to extend a heartfelt: Welcome back, Misterioso!